I spent quite a bit of time this fall talking about Super Tuscan and it got me thinking about the connection between tradition and terroir. Tradition is at the heart of European winemaking–when something has been tried and tested for fifteen or twenty centuries, it tends to stick around, sometimes without regard for absolute quality.

Terroir is supposed to be what informs tradition. The unique character of the soil, sunlight, climate, geolocation, and innumerable other factors will eventually inform grape growers which varieties will thrive and make the best wines in any location. Terroir goes off the rails when growers and producers quit asking if their wine could be better and simply stick with what was acceptable last time.

Case in point is the wine I’ve been promoting for weeks: Super Tuscan. Tuscany, arguably the heart of Italian food and wine culture, produces Chianti. Over time the recipe for Chianti calcified into a formula that was eventually made into law under the DOC rules, which mandated a maximum of 70% Sangiovese and at least 10% white grapes, harking back to field blending traditions. Unfortunately, although these traditions are charming and, well, traditional, they don’t make the best wine. Well-grown, low-cropped Sangiovese Grosso grapes would make far better wine by themselves, without the addition of the other grapes. No matter, according to DOC laws: that’s the way it would be done, forever.

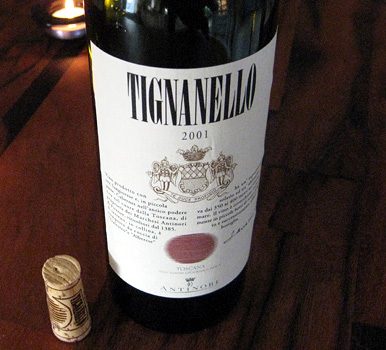

Until the Antinori’s got into the act. This Tuscan wine family deliberately set about breaking the law, delightful scoundrels that they were, and planted Cabernet Sauvignon in their vineyards. They blended it with Sangiovese (and no white grapes) and aged it in small, brand-new oak barrels rather than gigantic, characterless casks that were more typical of the general Italian winemaking techniques. The resulting wine, released in 1978 caused a sensation, on many levels. It had the hallmarks of Bordeaux–Cabernet structure, tannin and fruit, with well-developed oak and a distinct lack of Brettanomyces (an infection conferred from very old barrels, all too common in Italy at the time) and the length and dry finish of Italy, with an almost almond/cherry pit note.

On one of the other levels, the Italian wine authorities went mad. Super Tuscans could only be sold under the designation ‘Vino di Tavola’, a name reserved for wine only fit for people who lived under bridges or for wine used to put out fires. No matter: it was brilliant and delicious, and many other wineries followed suit, most notably Tenuta San Guido who made the well-regarded Sassicaia. The concept even spread to other Italian appellations, such as Piedmont and Veneto, and Super Tuscan wines sold for far more money than mere Chianti could command.

Realising the situation was beyond them, and that Super Tuscan was becoming a more credible and desirable brand than Chianti, the laws were finally changed so that by the early 90’s most of the wine could be sold under the Chianti designation, or the new IGT Toscana and DOC Bolgheri designations.

The upshot of the whole situation was that producers recognised tradition had trumped terroir, and by trying new grapes and new techniques, they could exploit the very best of their terroir to create something wholly new, and wholly better than tradition could deliver. Soon enough others copied their ideas, helping create the ‘Garagiste’ movement, a semi-sneering designation that connotes eccentric amateurs trying to craft fine wine from a humble garage.

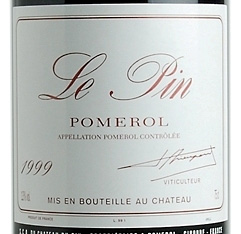

But craft they can. Chateau Le Pin in Bordeaux’s Pomerol appellation is only 5 acres and produces a spare 600 cases per year, but the wines are astounding, crafted in the fruit-forward new world style more common from Australia or California, very lush and showy, not at all a Bordeaux-typical wine, but like Super Tuscans it sells for more than other Chateau of higher rank, sometimes clocking in as the most expensive wine in the world.

As time passes and younger, less hidebound winemakers come on scene, more of these outlaw wines are coming to market. A few years ago I encountered a completely unexpected ‘Vinos Sin Ley’ (literally ‘wine without law’!) from Spain.

Utterly unexpected, it was another example of circumventing tradition to take old grapes and teach them new tricks: bold, rich and full of stunning fruit, it was nothing like the Riojas I was used to drinking, and I loved it so much I bought a case on the spot.

The latest example of lawbreaker wines is coming out of the Rhône in France. Famous for wines like Châteauneuf-du-Pape, there are 18 allowed varieties in their blends, but the stars are Grenache and Syrah. Upstart Chêne Bleu is repeating the successes of the other lawbreakers and crafting wines based on new techniques and an exegetic analysis of the potential of their terroir. I can only imagine that their wines are going to be amazing as well.

Tradition produces beautiful results. It gives us history, depth and a surety of outcome. But at some point tradition has to be examined for success, and have a light shone onto it to see what flaws time has revealed, and what new ideas and new thinking can bring. In the case of wine I’ve never felt that pitching out tradition willy-nilly benefited anyone, but likewise challenging results and exploiting the full potential of a vineyard’s terroir can only result in better wine.

Excellent Article, Tim!

I was thinking about experimenting and blending Nero D’Avola and Sangiovese Grosso. Do you know if that has been done before? Could be called Super Sicilian Tuscan.

Sky’s the limit, SP, and I think that would work out very well as an extremely Italianate wine. Call it SuperSicilian, Tuscany gets enough press.

Tim