It may come as a surprise to some people, but I have a few strongly-held opinions, among them that 90% of sour beers are awful, no country music worth listening to has been made since 1977, and that honey is disgusting.

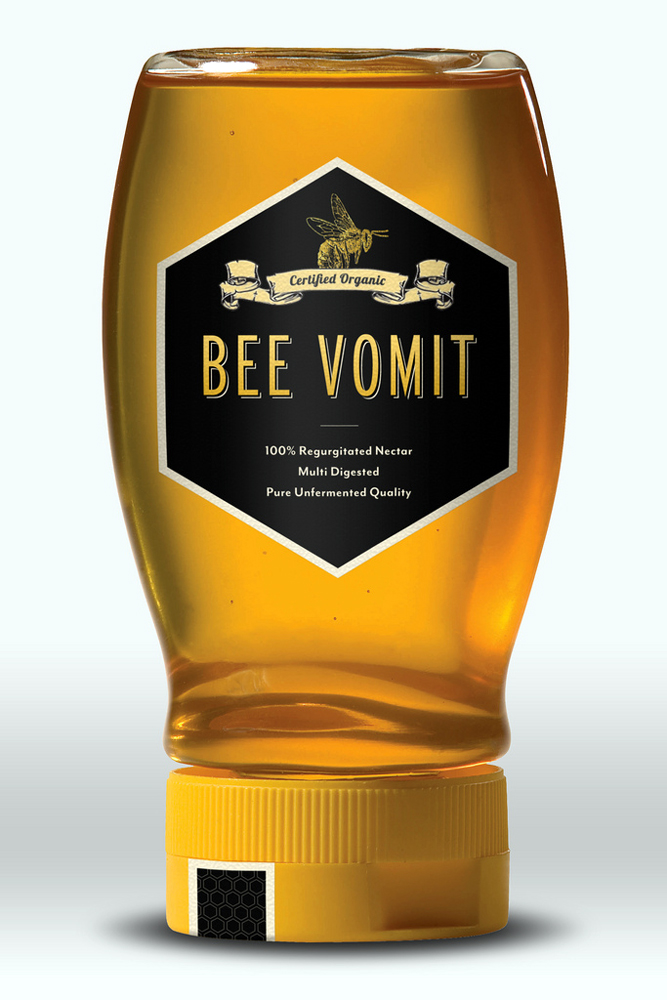

It’s not that I don’t like bees: I have an organic community garden and help support a half-dozen hives, planting flowers and borage to keep the girls in nectar and pollen. But honey . . . what do you call something an animal swallows, adds a bunch of body fluids and enzymes to, and then pukes back up?

In addition to the queasy aspects of eating something that’s already been eaten once, there’s the whole idea of exploiting the labour of indentured workers: 2 million flowers must be visited by bees who have to fly 55,000 miles to produce a single pound of honey and an average worker bee makes only about 1/2 teaspoon of honey in her lifetime.

So between my feelings on this and my repeated statements that I despise mead, I was asked by the organisers of the Pacific Northwest Homebrew Conference to give a lecture on making mead.

What is Mead?

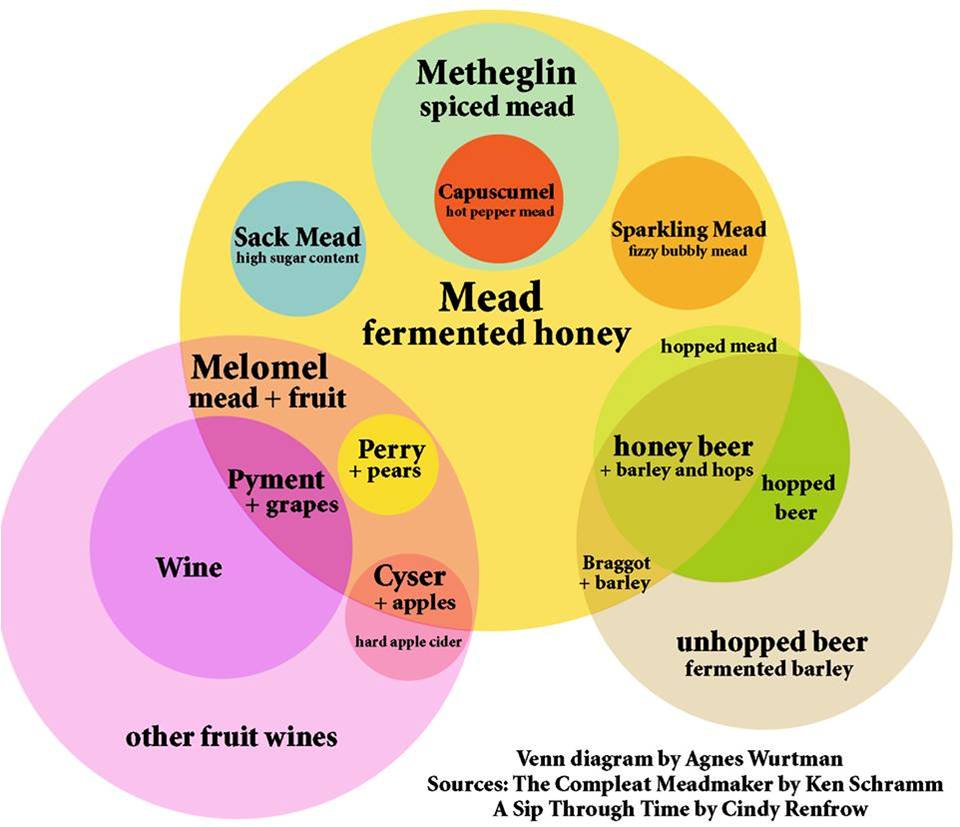

Mead is a fermented beverage made from honey. In its most basic form it’s just honey diluted with water, with yeast to convert the sugars to alcohol. It’s a very old beverage. Archaeometric evidence suggests that it might be the earliest fermented beverage.

Mead has a big share of historical imagination about beverages. The saga of Beowulf features mead and when Vikings died honourably in battle they were thought to wake up in a great mead hall (the mead came from the udder of a goat . . .) In addition, ‘honeymoon’ describes a gift of mead that newlyweds were given. It was believed their consumption of it over the following month would increase fertility.

Why Historical Mead is Awful (A Rant)

All of this romanticism about mead has made it popular with a certain class of enthusiast. Now, I’m not one to criticize Renn Faire devotees, but their uncritical devotion to mead as some kind of special beverage has left little room for the truth about it: most historical mead tastes exactly like other historical drinks: oxidised, poorly fermented, and badly balanced towards excessive sweetness and alcohol levels.

Think about it: mead came before wine, and co-existed with early cereal beverages. Beer made with ancient grains would rarely have been higher in alcohol than four or five percent, and would have been consumed at least in part for the rich, porridgey calories it gave. Fermented honey could exceed 10% ABV, sometimes even higher, intoxicating drinkers with a swiftness that nothing else did. It deserved the reputation it had.

But just as we no longer drink bowls of murky porridge through a filtering straw (true story) we no longer have to drink overstrong bee-juice for kicks. Modern brewers use a variety of recipes, techniques and post-fermentation interventions to achieve clear, stable beers that have more-or-less subtle and well-balanced flavours. If beer brewing was stuck where most amateur mead-making seems to want to stay, we’d all be crumbling up biscuits into clay pots on brew day, and drinking it three days later, before ‘demons spoiled it’.

In short, despite having judged mead many times, and tasting one truly, epically great mead, I had very little respect for it as a beverage, even if you left out the bee vomit.

Enter the PNWHC and An Ally

The Pacific Northwest Homebrew Conference is a riot. Much smaller than the NHC, it’s also easy to navigate, and the attendees are seriously enthusiastic and friendly to a fault. I attended the first year and had a great time, so when they contacted me to ask if I’d give a seminar, I gladly agreed. When they told me they needed a lecture on mead making, I instantly agreed, because this was my chance to see if I could influence meadmakers in a positive way.

Funny enough, in talking to my peers in the beverage industry they all agreed I was the perfect man for the job–or maybe they just thought it was delightful that a man who didn’t even eat honey should be forced to make mead and teach others how to do it. I contacted my old friend Jason Phelps for some advice and support.

Jason is a colleague from my days at Winemaker Magazine and founder of Ancient Fire Mead & Cider. He makes beer, wine and a lot of really excellent mead. Not only did he lend me his PowerPoint presentation, he also sent along a case of mead for my class to taste. That left me with making a couple of batches of mead of my own, to demonstrate my theories of ancient vs. new techniques, and the advantages of approaching mead like a winemaker rather than a brewer.

Don’t Make Mead Like a Brewer

Brewing is a craft derived from empirical observations, while winemaking is a science influenced by serendipity. The difference is subtle, but for me it comes down to the fact that brewers can control the starting conditions of their beers more-or-less completely by manipulating the grain bill, the mash schedule, the water chemistry, the hop additions, the yeast choice, etc. However, once they’ve pitched the yeast the number and kind of interventions they make to their brew drops off pretty steeply.

In winemaking on the other hand, the vintner is always at the mercy of his ingredients. some part of weather, climate, terroir, late rain, mold, bird attacks, et cetera, will influence the raw materials coming into the winery. Important interventions can be made to ensure a clean and healthy fermentation, but how all of the factors that go into a wine will eventually meld together can’t be completely predicted.

But it’s post-fermentation where a winemaker can work magic. The process of taking a wine after primary fermentation to being finished is called elevage. It’s a French term that means ‘raising’ or ‘upbringing’ and it’s applied to both children and livestock to mean the same thing: doing what you can to ensure the best outcome for something in your care. Acid balancing, adjusting sweetness and alcohol, fining and filtering adding tannins (or taking them out) preventing oxidation or re-fermentation, sur lie, battonage, barrel-ageing . . . the host of techniques goes on. Mead makers needn’t avail themselves of all of these, but approaching a mead like a winemaker who is shaping it as they go is an important distinction that separates us from the ancient ways.

Getting My Recipe On

The last time I had made mead was back in about 1984 (don’t laugh, I’m old) from a wadded-up photocopy of The Joy of Homebrewing. As a lark, and to make a friend happy, I followed the Barkshack Gingermead recipe from out of the book. My hazy memory of the drink was that it was extremely well-received, and I never made it again, because honey.

I hauled it out and inspected the recipe with the eye of thirty years as a winemaker.

- 7 lb Light honey

- 1 1/2 lb Corn sugar

- 1 oz To 6 oz fresh ginger root

- 1 1/2 ts Gypsum

- 3 tsp Yeast nutrient

- 1/4 tps Irish moss powder

- 1 lb To 6 lbs crushed fruit

- 3 oz Lemongrass, or other spices

- 1 pk Champagne yeast

Not bad, but there were some weird things in there, like gypsum (calcium sulfate) and Irish moss (seaweed) that didn’t make sense to a winemaker. Sure, gypsum would drop the pH, but there are more subtle ways to do that. Also, it was a lot of honey for what I was shooting for. My revised recipe looked more like this

- 4 lb really Light honey

- 3 lb sugar

- 6 oz fresh ginger root

- Zest and juice of one lemon

- 20 grams of tartaric acid

- 10 grams Yeast nutrient

- 5 lbs crushed fruit (rhubarb, raspberries)

- 6 stalks bruised Lemongrass

- 1 pk Belle Saison yeast

With a little luck, it would barely taste like honey at all.

Part Two: Assembling the Ingredients and Making the Mead

Wow, enjoyed waking up to that. We may be long lost cousins. Finally another craftsman who believes sour beer is just a ruse to avoid dumping a spoiled batch and that it takes a winemaker to produce consistently great meads. I’ll go one step further and say the BJCP should have nothing to do with guidelines for making or judging mead. Looking forward to part two.

Somebody has to work the guidelines, and the BJCP has a great infrastructure for it, but they do view it through the historical lens of beer.

But yeah, I hope that whole sour beer thing goes away soon.