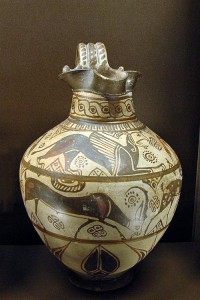

Making wine from a kit is an awesome way to become your own personal vintner. The kits provide all of the ingredients and materials to turn out a couple of cases of wine in less than a couple of months, and the instructions are complete, clear, and very easy to understand.

Ahem. Given that I wrote most of the kit instructions out there over the years, it’s understandable that I’ve got a positive feeling about them. However, I’m aware that not everyone thinks they are as clear as they could be, and it almost always seems there’s too much detail or not enough.

One area where it’s difficult to convey the exact intent is in stirring. When you reconstitute the kit on day one, it’s important to stir hard enough to mix the juice thoroughly–easy enough. On fining/stabilising day stirring is even more important: you have to agitate the wine hard enough to disperse the trapped carbon dioxide gas. If you don’t, not only will the wine be slow to clear, it will be fizzy at bottling time and will always have a slightly off aroma and flavour–that trapped CO2 will carry a bit of other, nastier gases with it, like hydrogen sulphide and dimethyl sulphide: rotten eggs and cooked cabbage respectively.

In actual fact, you shouldn’t ‘stir’ your wine kit. Stirring merely moves the wine around, like a lazy kid on a merry-go-round. You need to agitate the wine hard enough to get all of the gas out.

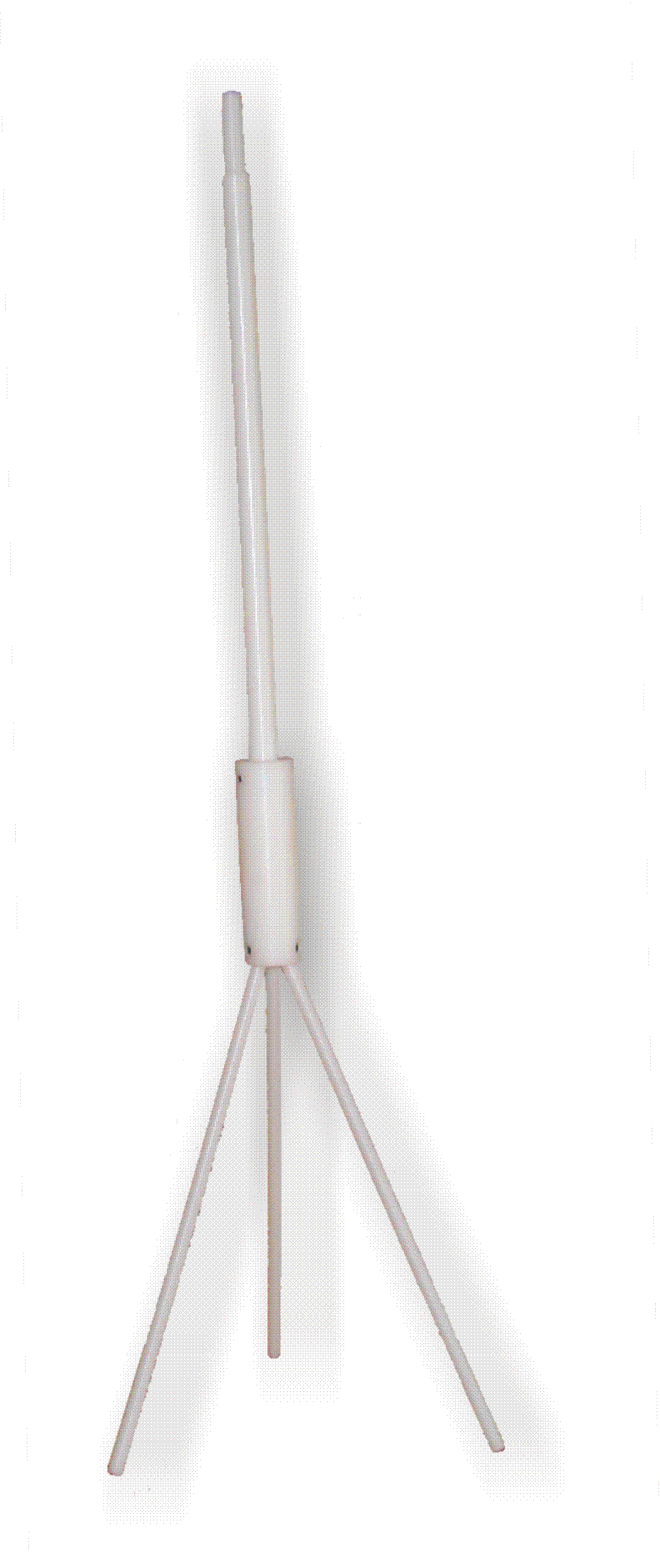

This is why I’ve always recommended a drill-mounted wine whip.

To use one of these, once it’s sanitised, the top goes into the chuck of a high-speed reversible hand drill (plug-in kinds are best–those battery jobs always seem to be flat when you need them) and the three prongs are folded and inserted into the carboy or bucket. When you’re de-gassing, you always use the whip at full power, except at the very beginning, when you test to see how much gas saturation the wine has. Everything is fun and games until you’ve got Krakatoa Cabernet fountaining out of the carboy and onto the ceiling. Sequence goes like this:

- Quick, one-second experimental stir. If things don’t instantly spray out of the carboy, proceed to step two.

Go absolutely full power, and keep it there.

Go absolutely full power, and keep it there.- When the wine begins to swirl up the sides of the carboy, looking like it’s going to overflow, immediately reverse direction, and go full power, against the flow of wine.

- You’ll see the wine stop climbing up immediately. Keep it on full until it starts to climb up again, and repeat the reversal–full power.

- Repeat this twice more, always full-on.

If your wine is not de-gassed at this point, it’s because the gods of fermentation hate you, or your wine was not finished fermenting, or your wine is very cold and it’s a bright sunny day (high barometric pressure). But I’m betting on some kind of divine divine vengeance because I’ve never needed more than three spins each way, less than two minutes altogether.

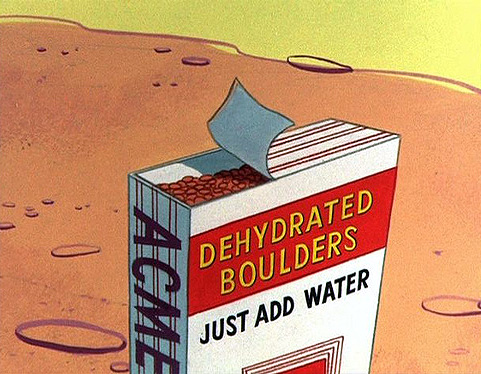

The point of intense agitation is to cause tip-vortex cavitation in the wine, at the tips of the whip. Cavitation happens when you vaporise a liquid by exposing it to decreased pressure. This vapour is the same thing as steam from a boiling kettle, but doesn’t involve heat–just the pressure reduction.

This is a little hard to visualise, but it obeys the laws of thermodynamics perfectly. The most common place to see cavitation is in boat propellers. Spin them up too fast and they won’t push the boat, because they’ll be in a cavity of water vapour, whirling about and doing nothing (unless they’re special supercavitating propellers, but let’s pretend they don’t exist).

For the last couple of decades I’ve been telling people about cavitation by quoting the 1990 movie The Hunt for Red October. It’s a techno-thriller about Soviet-era espionage and features Sean Connery as a Russian sub commander with a ridiculous Scottish lisp. In the fateful scene the commie sub tries to make a run for it but the propellers spin too fast and they cavitate. Why this is a crucial plot point is that during cavitation, when the vapour bubble collapses (as all good bubbles eventually do), they slam shut with such violence that they ‘hammer’ the water, which makes a large enough noise to alert enemy sonar operators. It’s this slamming/hammering effect that literally blasts carbon dioxide bubbles out of suspension, and why stirring any slower is almost useless for de-gassing.

(Not only does this make a really great echo for sonar operators who might be looking for Rooskies, in extreme cases it can cause sonoluminescence, a burst of photons [light] from the bubble collapse. You know why it does this? Good, that makes one of you. Nobody actually has a lock on the theory of why a collapsing bubble in a liquid makes light. It just does. Probably quantum, or Vogons or something.)

That analogy worked for the first decade, less well for the next, and now it doesn’t carry any weight with people under the age of twenty-five, who never lived with a Soviet Union, just a big old Russian crazy-quilt of ongoing collapse and oligarchic wealth transfer. I’ve been trying to find a new handle on the moment, and Just This Day I found one, courtesy of Smarter Every Day. If you’re not familiar with them, you’re welcome. Destin and his support crew demonstrate scientific and physical principles in extremely clear ways and film them (sometimes at twenty thousand frames per second!) and post them on YouTube. If you’re a science geek/covert nerd like me, that link is going to suck up a lot of your time for a while. My apologies to your family.

Here’s the video, in which they shoot an AK47 in an (empty) swimming pool.

It’s over ten minutes long, and while I urge you to watch all of this fascinating and brilliantly executed demonstration, if you’ve got a cake in the oven or are being chased by zombies, you can fast-forward to 4:30 for the most excellent illustration of the hammering effect of the bubble collapse. The AK47 bullet travels through the water, pulling a vapour bubble behind it. The bubble collapses, and as it does, you can actually see the intense shock wave that the collapse produces. And it hammers so hard, it rebounds and produces a secondary shock as well!

Imagine what being shot with a Russian carbine would do to a carbonated beverage. Yep, it would really go a long way to de-gassing it. And that’s the same kind of action you get when you stir your kit wine with a whip at full speed, only with less bullets and collateral damage.

The question could come up, ‘Why are you so hot on that three-prong whip, Tim? It’s much more expensive than the other drill-mounted stirring whips on the market–do they pay you?’

Alas, I only wish I got a commission on those things. I’ve been pushing them like a madman since I saw the first one. It’s purely a functional thing–the other models of whip work, but they’re not quite as effective, for a couple of reasons. First, most of the other whips cannot take the force of being reversed under full power. Their stubby little blades shear right off, or the hook-ish shaped ones twist themselves into a knot.

Second, if it’s the speed of the tip of the whip/propeller that makes the vortex appear, then spinning a set of three whips spanning a circle nearly a foot across at the same RPM as a wee stubby little set of blades will make those long whip-tips travel immensely faster–they have to to cover the same complete circle as the wee little ones, so they’re hustling much faster.

So there you have it. Please don’t fire an assault rifle into your carboy. Instead, get a drill and one of those amazing three-prong whips and you’ll be out of gas faster than a ’59 Caddy.